The origin of each colour through out time

History, origin and characteristics of each colour: from the first colours that ever existed to the ancient, classical world as well as medieval times until today.

The knowledge in this blog derives from the book Chromatopia, An Illustrated Colour of History, David Coles, Thames & Hudson.

The first colours

Ochres, chalk white, lamp black, bone white, bone black

Ochres

The oldest artworks (dating back 250,000 years) created by humans feature animals, humans, and spirits, drawn using ochres.

Iron ochres are derived from the earth. This mineral is dug up, smashed with a hard rock, and mixed with water. Later civilizations refined the process by cleaning the ochre of impurities, drying it, and grinding it into a fine powder. Yellow ochres can be roasted to become orange or red—often referred to as “burnt.” There is, of course, a wide variety of hues and transparencies.

Chalk white

Chalk can be used alone or mixed with ochres to brighten them and expand the color range. It was the primary white pigment until the ancient Greeks invented lead whites.

Chalk is a soft, white mineral, specifically calcium carbonate, formed from the fossilized remains of microscopic phytoplankton. It can be described as very thick.

Chalk was used to make gesso, a bright white plaster applied to wood surfaces, such as church altarpieces. Today, chalk is still sold, but it is chemically manufactured for industrial applications.

Colours of ancient times

Egyptian blue, orpiment, realgar, woad

Egyptian blue

Invented around the time the Great Pyramids were built—about 5,000 years ago—Egyptian blue was the first synthetic pigment made by heating lime, copper, silica, and natron. Initially used for glazing ceramics, it later found applications in murals, sculptures, and sarcophagi.

The pigment spread geographically to nearby regions, including Greece (used in the palace of Knossos, Crete), Pompeii, and Roman wall paintings. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the knowledge of how to create Egyptian blue disappeared but was rediscovered in the 1880s after Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt.

Orpiment

Known as the closest imitation to gold, orpiment's Latin name, Auripigmentum, translates to “gold paint.” It contains sulfide of arsenic, which is highly toxic. The Romans, aware of this danger, used slaves to mine it, leading to many fatalities. Ancient Egypt, however, utilized it in cosmetics and for paintings in Persia and Asia.

In the 17th century, a manufactured version of orpiment emerged from Arabic alchemy, called King’s Yellow. Use of orpiment declined in the 19th century with the introduction of less toxic pigments like cadmium yellow.

Realgar

Also highly toxic, realgar is known as the “ruby of arsenic.” Its red crystals are composed of arsenic disulfide. The name originates from the Arabic word Rahj-al-ghar, meaning “powder of mine.”

This pigment was favored by artists in Mesopotamia, India, and the Far East. In China, it was referred to as the masculine yellow, while orpiment was considered feminine. Due to its toxic properties, it was used as a rat poison during the Middle Ages and in China to repel snakes and insects.

Colours of the classical world

Lead white, tyrian purple, indigo, malachite, azurite, red lead, verdigris, chrysocolla

Tyrian purple

This color was reserved for the elite; in Imperial Rome, only the emperor was allowed to wear “true purple.” Those who owned purple garments without permission faced severe consequences.

Derived from the sea snail Bolinus brandaris, this dye has a history of approximately 3,500 years. Greek legend states that Hercules discovered the dye when his dog’s mouth turned purple after chewing on a snail.

Producing Tyrian purple required 250,000 snails per ounce, resulting in a horrible stench during manufacturing, which was often banished from towns. The method for preparing Tyrian purple was lost after the fall of Constantinople and was only rediscovered in 1998.

Indigo

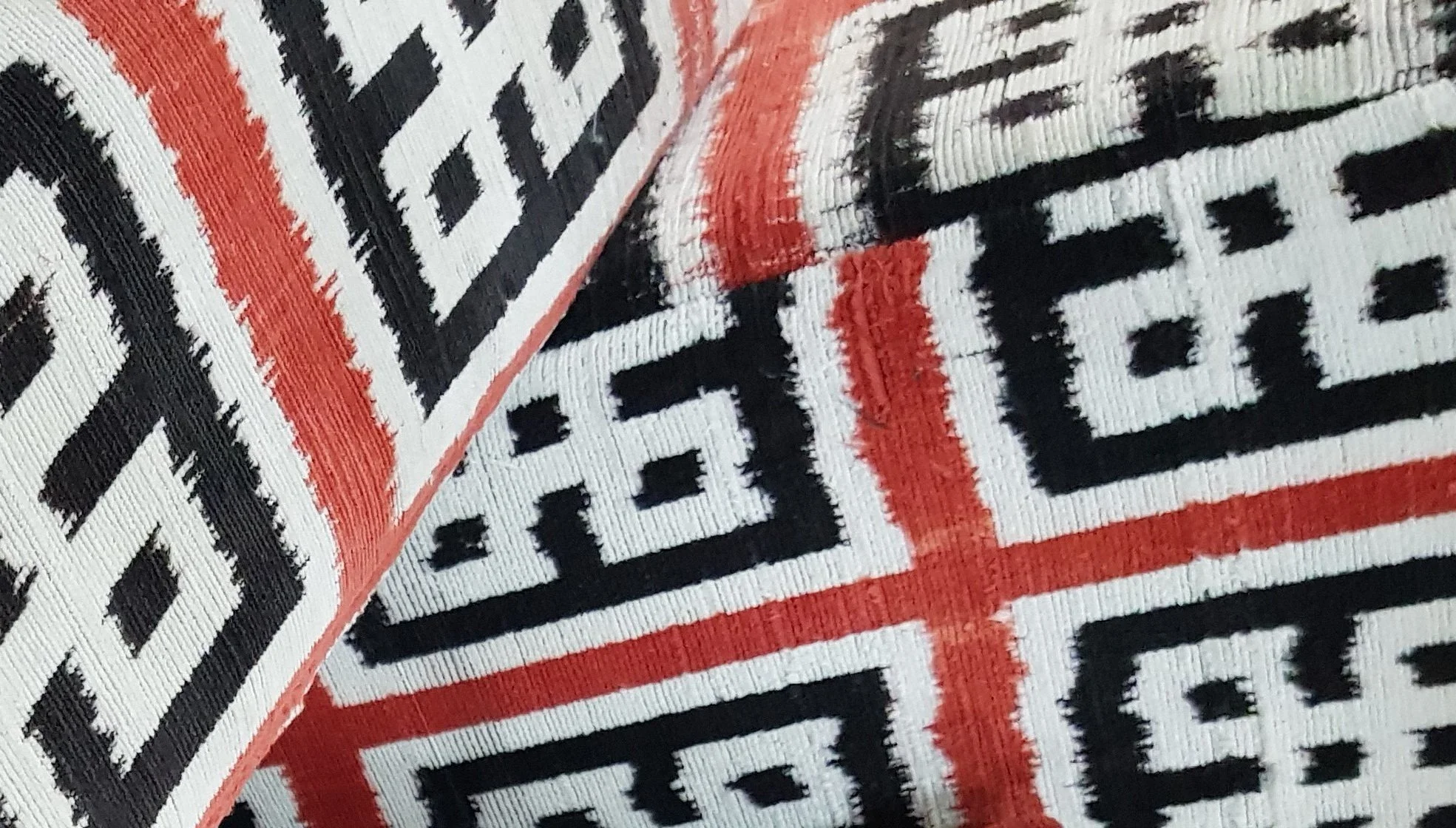

For several centuries, indigo was the most important dye, used for textiles and wall paintings in the ancient world. It is extracted from the leaves of Indigofera tinctoria, first cultivated in the Indus Valley over 5,000 years ago, where it was called “nilah” (dark blue).

The word indigo derives from the Latin term indicum (meaning “from India”). The production method involves soaking indigo leaves in warm water with an alkaline substance, then submerging logs with the leaves until the dye is drawn out through fermentation. When the water turns green, it’s transferred to a second tank, where workers beat the liquid to initiate oxidation, resulting in a precipitate that is then boiled in a copper cauldron until it forms a paste. Finally, the dye is dried and sold as cakes of “blue gold.” Synthetic indigo was developed in 1880.

Malachite

Until the 19th century, very few green pigments were available. Malachite, a copper carbonate, was one of them and was used in ancient Egypt for cosmetics and tomb paintings. Its production involves selecting, crushing, and grinding the mineral to a powder, followed by washing to separate the green particles.

Malachite remained important through the Renaissance but fell out of use in the 18th century with the development of synthetic alternatives.

Medieval colours

Lac, vine black, kermes, dragon’s blood, lapis lazuli, peach black, lead tin yellow, vermillion, malt, saffron, blue verditer, graphite, naples yellow

Lac

Lac, derived from the Laccifer lacca insect, was imported to Europe in 1220 and became the primary source of red during the Renaissance. By altering its pH level, lac could produce hues ranging from orange to violet.

Dragon’s blood

Extracted from the Socotra dragon tree (Dracaena cinnabari), dragon’s blood resin was used in medicine, alchemy, and as a colorant, primarily for varnishes (notably used by Stradivarius for his violins).

Peach black

This carbon black was created by charring peach stones, with other carbon blacks sourced from cherry, almond, walnut, and coconut. Roasted peach stones must be carefully managed to prevent ash formation. Peach black is recommended for watercolor use but not oil painting. An American chemist even developed a method for filling gas masks with activated charcoal made from peach stones to protect against chlorine gas during World War I.

Lead-tin yellow

For about 400 years, lead-tin yellow was the most important yellow pigment for artists.

Saffron

Producing just 100 grams of red saffron threads requires 8,000 handpicked crocus flowers. Saffron yields a strong, pure, translucent yellow that can imitate gold leaf, historically used to color the robes of Chinese emperors, as well as in wine, food, cosmetics, and medicine. Although synthetic pigments have largely replaced saffron, it has found a place in modern plant dyeing.

The colours on the wheel

Blue, Green, Purple, Red, Orange, Yellow

Blue

Due to the scarcity of natural pigments, early civilizations had to innovate. The ancient Egyptians created Egyptian blue through sophisticated techniques, marking it as the first synthetic pigment.

Blue was not recognized as a distinct color in antiquity; instead, colors were categorized more abstractly. In ancient Greece, blue was referred to as “melas,” meaning dark—viewed more as a value of darkness than a color.

The concept of primary colors is a modern interpretation, particularly in Europe. The Middle Ages saw blue gain importance, with ultramarine arriving in Europe in the 13th century. It cost more than gold and was derived from lapis lazuli.

By the early 15th century, linseed oil became a binder for paints, although it made pigments dull, requiring wine to enhance the mixture. In the 18th century, more blue pigments were introduced, including Prussian blue, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, and synthetic ultramarine.

Purple

Purple has long been associated with royalty, with Tyrian purple exclusively worn by the elite. The term originates from the Latin word “purpura,” which traces back to the ancient Greek “porphyra.”

Extracted from Mediterranean sea snails, this ancient dye was also used by the Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas for religious ceremonies. In Japan, purple symbolizes wealth, while in China, it historically represented aristocracy.

Impressionist artists in the 19th century began using purple for shadows instead of blacks, leading to what some called “violettomania.” The first synthetic purple dye was accidentally invented by Henry Perkin in 1856, and it was named Tyrian purple.

Red

Red has held various meanings across cultures and historical periods. Often associated with sacrifice, violence, and courage, it was linked to the Roman god of war, Mars, leading Roman soldiers to wear red. In many cultures, red has also been used for body paint, such as by Indigenous peoples of Australia.

While it can symbolize love and fertility, in Asian cultures, red often represents good fortune; for example, Chinese brides traditionally wear red wedding gowns.

In ancient times, colors were not labeled as they are today; they were ranked by tonal values, composition, origin, and usage. Sources of natural red pigments include oxide iron and ochre, with the latter being humanity's first red. The ancient Greeks developed a primary red pigment that was widely used in European painting until vermilion, made from sulfur and mercury, emerged in the 8th century.

Insects like kermes, lac, and cochineal, as well as madder roots, were also significant sources of red. In the context of the Catholic Church, red symbolized Christ’s blood, and it was also associated with revolutionary movements.

Orange

The name “orange” comes from the fruit, introduced by the Portuguese from Asia to Europe in the late 15th century. Prior to this, the color was described as a hue between red and yellow. The first natural orange pigments were derived from ochres, and realgar provided a rich orange pigment in antiquity.

The ancient Romans created the first synthetic orange pigments. In spirituality, orange symbolizes fire and inner transformation in Hinduism, while in Western culture, it conveys warmth, creativity, and activity. Interestingly, in China and India, orange was named after saffron rather than the fruit.

Claude Monet’s “Sunrise” in 1872 added brightness to the artists’ color palette, leading to the development of organic synthetic pigments in the 20th century.

Yellow

Ancient cultures used yellow to replicate the power of the sun, one of humanity's oldest symbols. For ancient Egyptians, yellow signified perfection; gold represented the flesh of the gods, often used to decorate the sarcophagi of pharaohs.

In ancient Greece, yellow was one of the four primary colors, associated with the sun-god Helios. Byzantine churches were adorned with gold icons, and in classical Greece, prostitutes wore saffron-dyed cloths.

While yellow is often linked to sunshine, optimism, and enlightenment, it also bore negative connotations during certain periods. In the Middle Ages, non-Christians were marked with yellow, and in the 20th century, it became a symbol of exclusion during the Holocaust (Jewish people were required to wear the yellow Star of David).

Yellow ochre is one of the earliest pigments, while modern chemistry has introduced colors like chrome yellow, cadmium yellow, cobalt yellow, and synthetic azo dyes. Interestingly, it is impossible to create dark yellows; adding black results in a greenish hue.

Yellow is the most luminous color in the spectrum.

Green

Green is abundant in nature. The ancient Greek word for green is “chloros,” which gives us the term chlorophyll, the pigment that enables plants to absorb light through photosynthesis.

Green symbolizes growth and fertility, representing youth and freshness, with historical associations with healing and protection. In Islam, green is considered a sacred color, while in Buddhism, vivid greens signify life, and faded greens are linked to death.

For centuries, authentic green pigments were derived from copper-bearing minerals like malachite and chrysocolla. Green and blue pigments sometimes lacked clear distinctions. In the 19th century, artists gained access to safe, readily available green pigments, moving away from the use of arsenic-based minerals.